Discovery is achieving excellent growth in profits (JSE: DSY)

Discovery Bank has posted positive earnings

Discovery has released a trading statement for the six months to December 2025. With the share price closing 7.6% higher on the day, you know it’s a goodie.

Normalised profit from operations is up by between 22% and 27%, while normalised headline earnings should be up by between 25% and 30%. Those are excellent growth rates.

If you dig a bit deeper, Discovery Insurance was one of the highlights (growth of 32% to 37%). Another bright spot is Discovery Bank, which looks like it made at least R65 million in profit vs. a loss in the prior period of R145 million. They are acquiring around 1,500 customers per day in the bank.

Along with solid growth in Discovery Life of 13% to 18%, this was good enough to propel Discovery SA forward by between 16% and 21%.

As for the rest of the growth, investors will love seeing Ping An up by between 33% and 38%. Vitality is up strongly as well overall, although elements of it were affected by currency movements (specifically Vitality Network in Japan).

Results are due on 3rd March. In the meantime, investors might treat themselves to a smoothie thanks to a share price increase of 25% over the past year.

A healthy balance sheet and solid earnings growth at Fortress Real Estate (JSE: FFB)

The total return (share price + dividend) over 12 months is above 40%

Fortress Real Estate is an interesting fund. They have logistics properties worth R24.1 billion, with exposure to South Africa as well as Central and Eastern Europe. They have retail properties in South Africa worth R11.9 billion. They also have a 14.2% stake in NEPI Rockcastle (JSE: NRP) worth R15.4 billion.

Like most property groups, Fortress has earmarked certain properties for sale. They note that conditions in the property sector are improving over time, so they are being patient with the sales in order to get the best possible exit. The results for the six months to December 2025 reflect like-for-like net operating income (NOI) growth in the retail and logistics portfolios of 6.7%, so I tend to believe them.

Vacancies are down, tenant turnover is up and the sun seems to be shining on the fund at the moment. For example, the retail portfolio’s like-for-like NOI growth of 7.0% is more than double the rate of inflation.

The performance for the interim period is strong enough to give the group confidence to upgrade distributable earnings guidance for the full year. They now anticipate growth of 10% for FY26.

For the interim period, distributable earnings increased by 16.7% and the interim dividend per share was up by 15.4%. There’s a scrip dividend alternative (shares instead of cash for the dividend), priced at a 3% discount to the volume-weighted average share price.

The shape of KAP’s income statement has changed (JSE: KAP)

The focus on margin is paying off – but there’s much work to be done

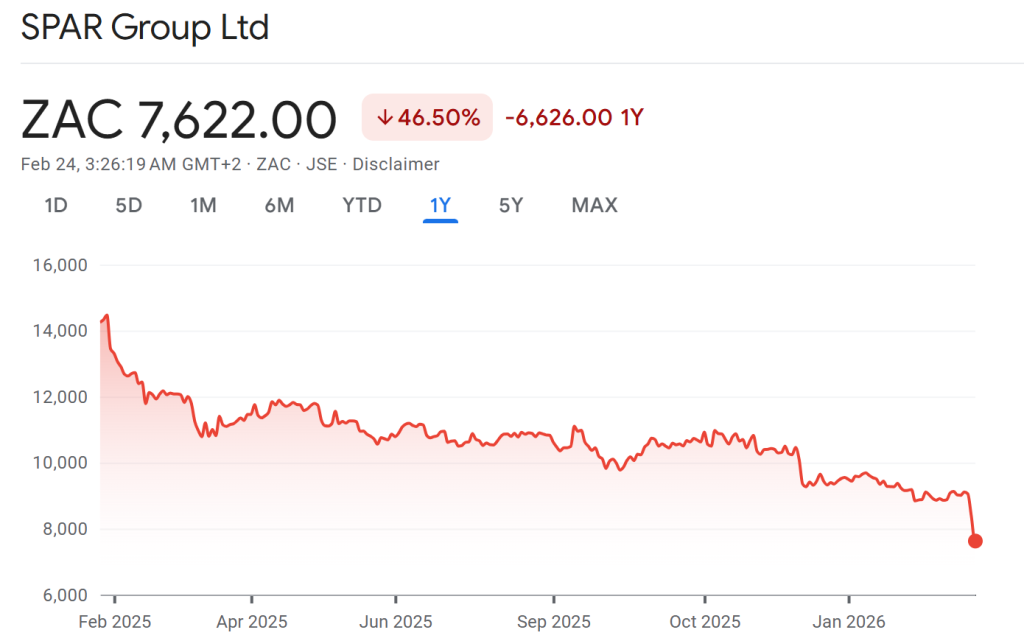

When KAP first gave an indication of its earnings for the six months to December 2025, I ran a poll at the time asking about your views on the company. Here are the results:

That’s a bullish view, with only 11% of people believing that something will go wrong from here. But to really get momentum in the share price, the company needs to get more people in the 44% fence-sitting category to get on the bid and become shareholders.

The decrease in revenue of 3% is unlikely to convince those investors, but perhaps the jump of 32% in HEPS will pique their interest. This was driven by a 10% increase in operating profit despite the revenue pressure. It’s also worth highlighting that cash generated from operations was up by 39%.

To be fair, the base period was severely impacted by the ramp-up costs at PG Bison’s new MDF facility, as well as a horrible situation for Feltex in the local vehicle manufacturing industry. Both of these issues have improved, hence the jump in profits for the group.

PG Bison’s operating margin is up 160 basis points to 15.2%, with a revenue increase of 18% in that segment doing great things for profitability. And at Feltex, operating profit increased dramatically from R42 million to R146 million thanks to a 23% increase in revenue.

As for the revenue pressure, Safripol is largely to blame here. The company suffered an 18% reduction in revenue and a 40% drop in operating profit. The operating margin is just 4%, so a drop in revenue in this low-margin segment can be mitigated by revenue in other, high-margin segments. This is why we’ve seen such a change to the group margin.

Unitrans also contributed to the change in group margin. Despite revenue decreasing by 8%, operating profit was up 3%. They are focusing on margin, not revenue for the sake of revenue.

Sleep Group grew revenue by 5% and operating profit by 4%, with the company even attributing the weak demand to online gambling. If retailers in South Africa are to be believed, people are practically sleeping on the floor in order to have money for gambling. I know it’s a problem out there, but I still think that it’s at least partially just a convenient scapegoat. In any event, 5% revenue growth isn’t a bad outcome!

But there is one bad outcome: Optix continues to disappoint. Revenue fell 11% and the operating loss widened from R18 million to R43 million. We keep hearing about how things are going to improve at this investment. It’s becoming a larger and larger pimple, right in the middle of KAP’s nose, and at a time when the market is actually starting to look more closely at KAP’s performance.

They expect the second half of the year to be softer compared to the first half. They will hopefully manage to keep margins at decent levels.

KAP is down 9.5% over 12 months, but up 25% year-to-date!

Much better numbers at Libstar (JSE: LBR)

They carried on where they left off in the first half

Libstar has released a trading statement for the year ended December 2025. They had a solid first half to the year, so the market was hoping that the momentum would continue. The good news is that it did!

With the fresh mushroom operations being sold, that part of the business has been recognised as a discontinued operation. Keep that in mind when thinking about the percentage ranges.

With areas of the business like Perishable Products and Wet Condiments doing well, total HEPS is expected to increase by between 19.6% and 24.6%. The performance was helped along by a reduction in finance costs, made possible by strong operational cash flows that took pressure off the balance sheet.

Normalised HEPS from continuing operations increased by between 20.7% and 23.7%. It’s good to see that the normalised number isn’t terribly different to the number without adjustments.

It’s not all good news – there was still a large impairment that left them in a loss-making position in terms of EPS. The Ambassador Foods snacks business looks like it suffered an impairment of over R200 million.

It’s still a much better set of numbers than we are used to seeing at Libstar. The company is still trading under cautionary based on negotiations with potential acquirers of the group. Whether or not a deal will materialise remains unclear.

There’s only slightly positive growth at Nedbank (JSE: NED)

But it’s better than the market expected

Nedbank’s share price closed 8% higher on Thursday. This is a great reminder that share price moves are a function of expectations vs. reality, not just the underlying reality.

The trigger for the move was a further trading statement, in which Nedbank confirmed that diluted HEPS would increase by between 0% and 4% for the year ended December 2025. Not exactly exciting, is it?

Return on equity (ROE) is expected to be between 15.3% and 15.5%, down from 15.8% in the prior year.

The other important metric is of course net asset value (NAV) per share, which increased by between 3% and 5%. The NAV per share is between R247.60 and R252.41, while the share price is currently at nearly R315.

These numbers reflect a bank that is struggling to grow, but they were still ahead of the market’s even more bearish expectations.

The reason for the share price trading at a premium to NAV is that the ROE is well above the return required by investors on Nedbank. This means they are willing to bid up the price until it reaches an effective return that they are happy with.

The mid-point of the NAV guidance is almost exactly R250, so the share price is trading at 1.26x NAV (or book value). Based on ROE of 15.4% at the mid-point of guidance, the effective ROE (calculated as 15.4/126) is 12.2%. In other words, investors are paying a premium to NAV that gives them an effective ROE of 12.2%, as they pay R126 for every R100 of NAV, and earn R15.4 on that amount.

It’s not a simple concept, but I felt it was worth giving it a go. This concept is a major driver of bank valuations.

And in case you’re wondering why Nedbank would release a trading statement for such a small move in HEPS, it’s because the really big move is actually in Earnings Per Share (EPS). Due to the accounting treatment of the disposal of the stake in Ecobank, EPS will decline by between 52% and 55%.

Earnings are up at OUTsurance, but their Australian business had a very tough period (JSE: OUT)

Storms and catastrophe events severely impacted Youi’s margins

One of the many standing jokes in South African investment circles relates to how Australia just continues to hurt the people who invest there. One of the (very few) exceptions has been OUTsurance, who built the Youi business from scratch in that market. Building instead of buying has been key to success.

But even Youi can have a rough year, especially as an insurance company that has to retain some of the risk on its balance sheet in order to earn an underwriting margin. Thanks to catastrophe events and storms in Australia (as though the spiders and snakes weren’t bad enough), Youi’s normalised earnings for the six months to December 2025 were down by between 40% and 46%.

When you consider that Youi contributed more than half of the group numbers in the comparable period, that’s a scary decrease.

Thankfully, OUTsurance SA came to the rescue, just like they do when the robots aren’t working in Joburg. Earnings growth of 66% to 72% in that business did a spectacular job of offsetting the Youi pressure. In fact, it was enough for the OHL Group to be up by between 10% and 15%!

Although there were high-quality sources of earnings growth in South Africa (like increases in gross written premium and a better claims experience), I must note that the South African results were helped along by a change to share-based payment structures. This is good for shareholders, but would presumably have the largest impact on the implementation of the new scheme (i.e. in this period) rather than on an ongoing basis. In other words, the incredible growth in South Africa probably isn’t an indication of realistic growth rates in years to come.

Looking at the two smaller parts of the business, OUTsurance Life was flat, with a performance of -2% to 4%. This was mainly because of the change in the South African yield curve, rather than a reflection of the underlying sales performance. OUTsurance Ireland is in the incubation phase, with losses worsening by between 18% and 24%. They expect the losses to moderate in the second half of the year.

As an additional complication, OUTsurance Group as the listed company only holds 92.8% of OHL, which is where the abovementioned operations sit. There are also other balance sheet items that sit at group level, so the results are impacted by the performance in OHL as well as any other movements that sit above OHL.

Normalised earnings per share for the group increased by between 4% and 10%, while HEPS was up by between 11% and 17%. OUTsurance believes that normalised earnings is where you should focus.

The share price is only up 3% over the past 12 months. OUTsurance is an excellent business, but it trades at a demanding valuation.

Tasty mid-teen growth at Spur (JSE: SUR)

This has been a fantastic growth story in recent years

I’m a dad, which means that Spur is a place where I find myself every few weeks or so. It’s just one of those things. Parenting is both rewarding and challenging, with Spur waffles helping to grease the wheels of procreation.

The company knows exactly what they are doing, with a focused strategy that can only leave Famous Brands (JSE: FBR) investors with a bad taste in their mouths. Just look at the outperformance over five years:

Spur’s triumphant share price chart looks set to continue its journey, as the latest results for the six months to December are strong. Revenue is up 8.5%, HEPS increased by 13.6% and the interim dividend was up 13.2%. Cash generated by operations increased by a delightful 21.1%.

Customer count is up for the period, with average spend per head growing above menu inflation. Like I said, it’s those damn waffles.

Jokes aside, it’s actually the pizza. Panarottis was the star of the show, with restaurant sales growth of 17.4% for the period. Spur was good for 7.2%, while RocoMamas increased 4.9%. I’m afraid that John Dory’s remains poor, with sales down 11.7%. The Speciality Brands segment, which includes Hussar Grill and Doppio Zero, grew 9.1%.

One of the uncertain items is the contractual dispute with GPS Food Group. Although arbitration proceedings have supported the merits of the claim, the quantum hasn’t yet been determined. With two separate claims of R167 million and R95.8 million, we aren’t talking small numbers here. As Spur is appealing the arbitration outcome, they haven’t raised a liability at this stage. Just keep this in mind as a potential negative “surprise” down the line.

I’m keen to get your views on Famous Brands vs. Spur:

Tiger Brands is focused on efficiencies (JSE: TBS)

A price-deflationary environment means that only the strong survive

Tiger Brands released a voluntary update for the four months to January 2026. In an environment of low inflation in core products like bread and cereals, it’s really difficult to achieve significant revenue growth.

Revenue from continuing operations increased by 1% year-on-year. Volumes were up 2% and price had a -1% impact – your eyes do not deceive you, that is price deflation! They’ve continued to clean up the product range, with volumes up 5% if you focus only on the SKUs they will have going forward.

Revenue growth was achieved in all business units except for Home and Personal Care, where competitive forces were severe. They expect that to get better in the second half of the year based on turnaround initiatives.

Despite the subdued revenue growth, gross margin was up. This drove growth in operating profit, with a double-digit operating margin. Benefits in areas like supply chain costs also contributed to the growth in margin.

The optimisation of the group remains the focus. This includes transactions like the disposal of the Cameroonian subsidiary, Chocolaterie Confiserie Camerounaise S.A. (Chococam). They are also deciding what to do with Beacon Chocolate and King Foods, which remain in continuing operations for now.

Although some of the share price pressure this year is because of the significant special dividend that was paid in January, there’s also evidence of profit-taking here. The share price closed 6% lower on Thursday in response to this update.

The anaemic results at Truworths continue (JSE: TRU)

They appear to be incapable of addressing the slide in Truworths Africa

Truworths trades on a Price/Earnings multiple below 8x. This isn’t because of market apathy, or because of unreasonable bearishness among investors. It’s because the only thing propping them up right now is the Office UK business – and the market knows exactly how vulnerable these offshore stories can be.

For the 26 weeks to 28 December 2025, Truworths Africa suffered a revenue decline of 3.6%. They are down in almost just about every category, making it clear that they have no idea how to stem the bleeding in the local business. Office UK grew sales by 7.1% for the period, which was just enough to perfectly offset the decline in Truworths Africa.

In terms of sales channels, online sales were up 23.3% in Truworths Africa and contributed 7.4% of sales. Office UK’s online sales were up 7.5% in local currency and contributed 45.7% of total sales (the UK online market is mature vs. South Africa).

The Office UK growth vs. Truworths Africa decline led to flat sales at group level, accompanied by a steady gross profit margin of 51.8%. At least this is an area where Truworths Africa showed some improvement, with gross margin up from 53.6% to 54.0%. Office UK’s gross margin dipped from 48.2% to 48.0%.

Group trading profit increased by 2.8%, with margin up from 16.8% to 17.2%. Cost control in Truworths Africa was probably the highlight of this result, with trading expenses down 2.6% excluding forex losses.

By the time you reach HEPS, you find an increase of 1.3%. The dividend was up by a similar percentage.

For the first seven weeks of the second half of the year, sales in Truworths Africa were up by 0.6%. Compared to the decline in the first half, this is cause for celebration. But here’s the problem: Office UK’s sales were down 1.7% in rand terms despite being up 3.4% in local currency. An investment thesis based on one offshore entity is extremely vulnerable to issues like forex movements.

The Truworths share price is down 24% over 12 months. They are up 6.7% year-to-date, with the share price trying (and failing) to break above R61.

Nibbles:

- Director dealings:

- A prescribed officer of Reunert (JSE: RLO) sold shares worth R1.6 million.

- An associate of a director of KAL Group (JSE: KAL) bought shares worth just under R1 million.

- An associate of a director of Goldrush (JSE: GRSP) bought shares and CFDs worth R745k.

- A director of Calgro M3 (JSE: CGR) has bought shares worth R175k.

- Sygnia (JSE: SYG) has suffered yet another change in top management, with the company struggling to give investors much consistency beyond the almost-guaranteed presence of founder and CEO Magda Wierzycka. The latest is that Rashid Ismail has resigned as the financial director of the group. A replacement hasn’t been named as of yet.